Article “Life on the edge of Kibale Forest” by Charlotte Beauvoisin. Images by Julia Lloyd

Article “Life on the edge of Kibale Forest” by Charlotte Beauvoisin. Images by Julia Lloyd

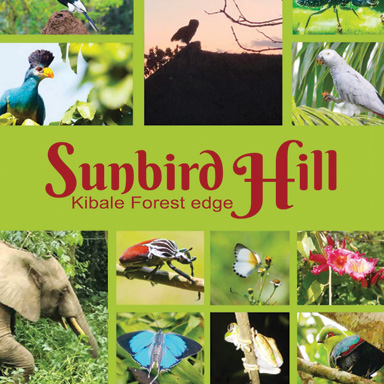

Charlotte Beauvoisin, author of Diary of a Muzungu is “blogger in residence” at Sunbird Hill Nature Monitoring Site on the edge of Kibale Forest, western Uganda. She writes about what keeps her up at night: elephants!

The boundary of Kibale National Park is just a few hundred metres away. The sound of a single tree falling is amplified across the dip in the ground that separates us from the forest. I recall some of my favourite experiences here:

One morning, we followed a tunnel of crushed vegetation on the edge of the forest to find a large pile of moist elephant dung. A round yellow object protruded from it. Sebastian dug out the jackfruit seed with the toe of his gum boot. “See, this is what the farmers have been saying to the Uganda Wildlife Authority. This jackfruit seed is proof that the elephants have crossed from the forest onto the farmer’s land.”

It was exactly this kind of evidence that was filmed and sent to the Parliament of Uganda to lobby for protection from the elephants. After a decade of pressure from the local villagers, the Uganda Wildlife Authority employed 64 men, plus another 10 from the community, to start digging a protective trench along the park boundary, ostensibly to keep elephants inside the forest and stop them raiding the villagers’ crops.

Elephants can’t resist jackfruit and maize. The scent of the crop carries and the elephants will carve a route until their forage is successful. What doesn’t get eaten, gets trampled. Find an elephant’s footprint and try it on for size. These fellows are even bigger than you think: a grown woman can easily place both feet in one elephant footprint, so can you!

One night, heads buzzing with questions, we venture down to the forest edge. Julia carries a big flashlight and scans the vegetation ahead of us. This season is more interesting than usual as we contemplate how the elephants will react to the trench. Seen from the tall viewing platform, the trench cuts a red scar across the landscape, delineating the boundary of the ancient forest from farmland. Here the earth is rich in minerals. Butterflies love the freshly turned earth and flutter through the sunlit air above the trench.

Activity is always at its most dramatic around the time of the full moon. The night air around Sunbird Hill’s 40 acres of forest edge habitat is filled with the shouts of farmers and their children, warning the mammoths to retreat from their land. The dogs are quick to alert us to visitors of all species. Nobody got much sleep the night the moon shone its brightest. The elephants were so close, we could hear the swish swish swish as they pushed through the tall aptly-named elephant grass.

How do the elephants know of the trench and the danger it represents to them? Were they aware of the men who dug barefoot along the forest edge? At 2 km long, two metres wide and two metres deep, might an elephant come crashing out of the forest straight into the hole? (What if Julia and I get to the edge of the trench and there’s an elephant stuck in there!)

With these thoughts in mind, we exit the sanctuary of the family compound and head for the Birder’s Lounge, a free-standing thatch construction a hundred metres from the forest. I half picture an elephant seated on the sofa! Out of the blue, chimpanzee ‘pant hoot’ cries make me jump and I laugh at my overactive imagination. I recall how elephants trashed the wooden fence one time. The family compound has a 9 feet high wooden fence on all sides, erected to keep the dogs in. It’s been propped back up again but looks like someone (something?) has sat on it.

Julia stands still in the full moonlight and scans every corner of the gardens ahead of us. Nested chimpanzees pant hoot in the distance. Julia knows chimpanzees but she also knows elephants. For many years, her home was a treehouse in the middle of Kibale Forest from where she led the team that habituated Kibale’s chimpanzees for tourism.

“Hang on Charlotte,” she says. “Don’t go racing down to the trench. Elephants may be big but they can appear silently out of nowhere.” She recounts a story of being in the forest one night. The elephants were ahead of her – or so she thought – until she realised she was standing right next to one. She couldn’t sprint to safety fast enough!

The morning after our search for elephants, I notice the heady smell of rotten quasi alcoholic fruit. At my feet is the scattered peel of a ripe jackfruit. These large ugly fruits hang like tumours on the side of tall trees. They have a hard spiky exterior and their inners ooze a heavy sap. They reveal the sweetest of fruits – just ask a baboon.

The impact of elephants visiting the community can be devastating. Local lad Sebastian tells me how he almost dropped out of school after elephants invaded their land and destroyed his farmer’s maize field.

Without it, there is no money for school fees. Sebastian started school two weeks late that year as his dad looked for a loan to continue his son’s education. How will his father be able to repay the loan if the elephants return this year?

Sebastian’s story is very common around here. Elephants are responsible for many children dropping out of school, consigned to a life without education and fewer opportunities. There are few paid jobs in rural areas and families survive on what they can grow: Irish (potatoes), yam, sweet potatoes, cassava, maize, beans, bananas and pineapples. You can understand why the elephants are tempted out of the forest for they won’t eat chilli, coffee or tobacco – but neither will the farmers’ children, hence the edible crops continue to be planted, despite the high risks.

I have lived in Busiriba (the village near Sun bird) and in Businge, Kasenda at the edge of the park. I love the elephants for the tourism they create. I hate them for the destruction they cause. I have lost things from jackfruit trees (the elephants brake a tree, just to get a fruit), lost numerous eucalyptus trees, bananas etc.

Unlike most neighbors I am able to complain and engage UWA but 99% of the time you get zero help. UWA rangers will tell you to call them when elephants come (effectively making you an elephant guard).

Elephants have learnt to fill the trenches with trees and rocks to create a “bridge” to cross over the trench! We’ve also witnessed situations where they help each other out of the trench, come destroy crops and cross back into the park. It is a bad and sad situation